A Journal from Vietnam

In October 2017, our Editor in Chief Jake Schneider and Poetry Editor Greg Nissan flew to Vietnam to attend the second edition of A-Festival, an independent festival of international poetry and translation, in Hanoi and Saigon. Here are some extracts from Jake’s journal of that whirlwind week.

10 October 2017: Berlin to Moscow to Hanoi

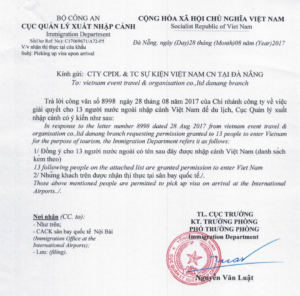

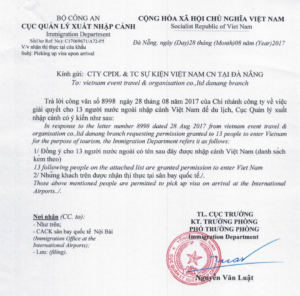

At the gate in Schönefeld, the gate agent was stymied by our travel plans: “Hanoi with US passports? Tricky.” (No Russian visa, either.) We struggled to explain our printed-out visa letter with its official stamps from the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, its sprinkling of accents on every vowel, its three-page list of invited foreigners. We were the last to board the plane.

The international airspace between Berlin and Moscow is what most people in Berlin mean when they say East: the former Soviet Empire, that competing cultural and economic center of Western Eurasia holding out an unsteady truce with the “West.” The Aeroflot logo is still a winged hammer and sickle, radiating Russian colors across the fuselage. To pass the time, I started translating excerpts of an Austrian novel that will be read at a festival in China next month. I thought I should get started because my deadline is early to accommodate the Chinese censors.

On this plane the supremacy of English was contested. The opulent sky catalogue restored Russian to its rightful place. As we descended, I looked at the constellations of tower blocks and thought, 75 years’ worth of this country’s buildings date from the communist era. But then, with the expanses of Moscow in the distance, we crossed neighborhood after neighborhood of mansions, tennis courts, small palaces, and even swimming pools on our way down.

11 October: Hanoi

Our driver from the airport, probably annoyed at our delay collecting our visas, wove through traffic, honking quickly each time he cut someone off, as if to say, “Excuse me” or “I’m here” or “Move out of my way.”

*

In the elevator of the Impressive, we played rock-paper-scissors for our pick of the rooms. I went for paper, because of literature. Greg thought rock because of the monumental church down the street, but threw scissors instead and cut up my literature.

*

The trick to crossing the street here amongst the uninterrupted flow of cars and mopeds is to walk slowly, steadily, unwavering, suicidally – and traffic moves around you. It’s like the Matrix.

Along with only China and North Korea, Vietnam is both brands of East. The flag bears the Maoist star, but the hammer-and-sickle is nearly as common. Schoolchildren wear uniforms with red scarves knotted at the neck – just like the blue neckerchiefs of the East German Jungpioniere.

*

The pre-opening opening event of A-festival was a screening of an experimental film called A Useless Fiction by a Cantonese-speaking Macao native, Cheong Kin Man.

It started with Kaitlin Rees and Nhã Thuyên singing “Ah” and we all joined in at different pitches.

The subtitles and competing languages on screen made up a kind of motion-picture Talmud, with Chinese and Korean going down the sides, English and Vietnamese on the bottom, Portuguese interludes, the occasional centered quote, and sometimes languages like Thai and Georgian, even Schwäbisch, thrown in. It was overwhelming.

Some of the film had been shot through a Post-It note on a cell-phone camera. Other parts were clips from documentary talking-head interviews, except the filmmaker didn’t let the talking heads (apart from one Macanese-Brazilian woman) talk. He had chosen that one woman at random from all the interviews, he told us afterwards on Skype.

Cheong, who lives in Berlin, was very confused and disoriented by the long-distance Q&A. In the end, after too many questions that were too frustrating for both sides, he asked us if we had the aircon on here and spoke about the temperature differences between Berlin and Hanoi. We were in different places and time zones, experiencing different ambient environments.

12 October: Hanoi

A long walk through the communist grandeur of the boulevards leading to the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum complex, guarded by motionless guards in white uniforms who aren’t even allowed to scratch themselves. (The more junior ones in olive drab were much less decorous: yawning, leaning, being human.)

Uncle Ho is in Russia for his annual servicing, so his tomb was closed. Instead, we looped round in the hot sun past the Imperial Citadel, party headquarters (hammer-and-sickle flag), and the Presidential Palace to the café outside the Botanical Gardens, where I insisted we sit a while under the plastic shade cover. We took off our shoes to remember the developments of the day so far: recollecting is a barefoot task.

*

The evening, according to the packing-tape schedule on Kaitlin’s arm, went as follows:

Aaaa

why a aaaa lai

what is a fest

thank you

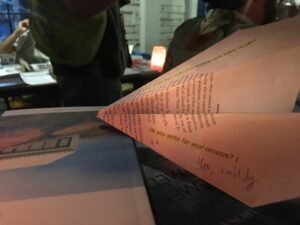

question planes

Dinner

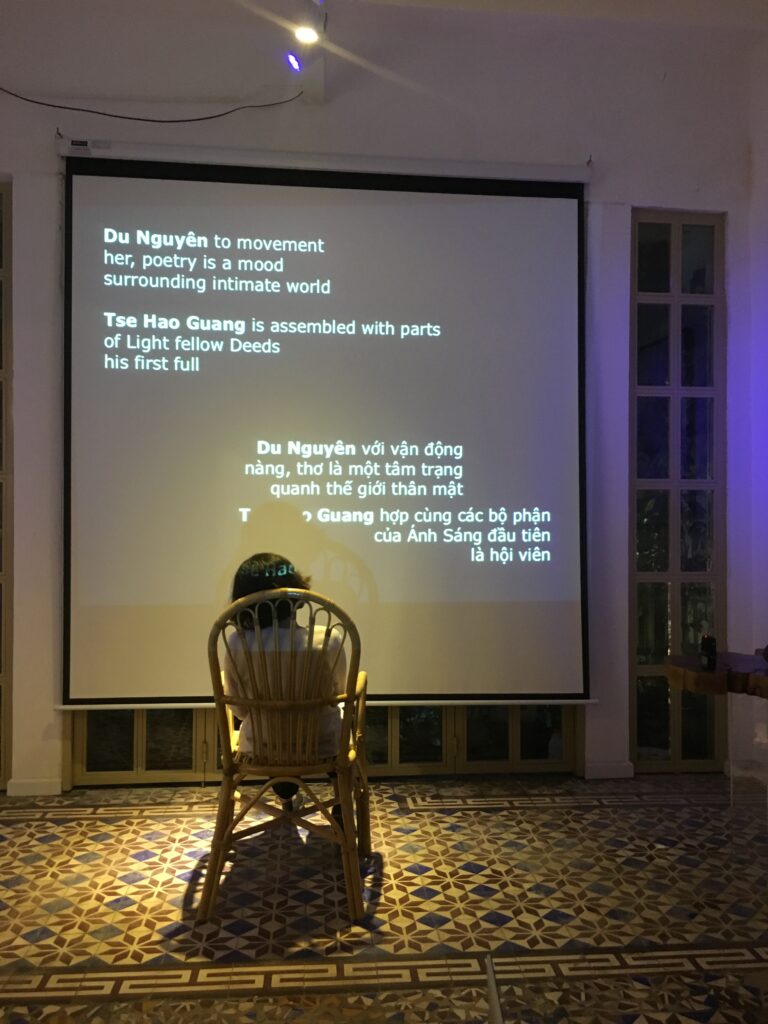

downstairs intro read

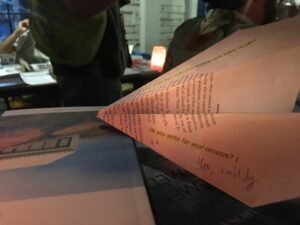

The question planes were questions written on paper airplanes, which we flew all around the bookstore despite the many candles burning in paper bags – which sometimes burned the bags themselves. The projector projected a constant loop of poetry on top of the readers’ faces and bodies. Questions like: Are you translatable? Do you write for your censors?

Video of the paper airplanes

At dinner, I learned that all publishing is censored here and there are heavy fines (like $1000) for making a mistake such as printing a map that leaves out disputed islands. This results in serious self-censorship by what independent publishing there is, which does not officially exist. AJAR is not officially anti-anything, but they don’t play by the rules either, so the secret police attends all their events. Once they got a big book order and noticed the delivery address was the police station. [When Thuyên and Kaitlin read this, they mentioned that about sixty of their books were once stolen/confiscated from a shop in Saigon. Kaitlin said that paper recycling collectors buy confiscated books from the police, and T & K considered trying to track them down and rescue them before they were pulped.]

Do you write for your censors?

I thought of the Chinese censor who will be reading my Austrian translation, but also a censer for wafting incense down the aisle of a church.

*

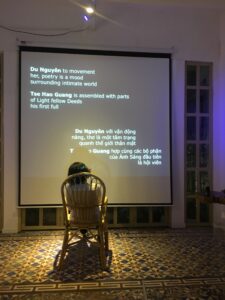

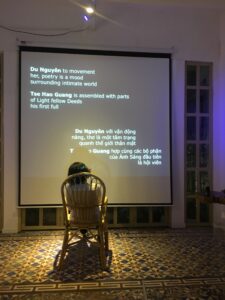

At the lengthy reading afterwards, each reader drew the next one’s bio out of a jar and read out some random keywords from it that gradually identified the person. Most readings were in English, a few in Vietnamese.

It closed with Thuyên’s adorable son Yen San reading from a Vietnamese picture book. (He and another little boy had otherwise been throwing paper planes all night and reading comics.)

Alec gave a deep explanation of Vietnamese relationship pronouns. Whenever you meet someone, you need to know their relative age (if it’s unclear) and you become older sister/younger brother, grandmother/granddaughter, uncle/nephew, etc. Apparently when speaking to an American, they even throw the English word “you” into the mix.

Alec said he’d say “bro” or “man” in English, and I said those words were markers of heterosexual masculinity. Ways of showing distance and proximity at the same time.

13 October: Hanoi

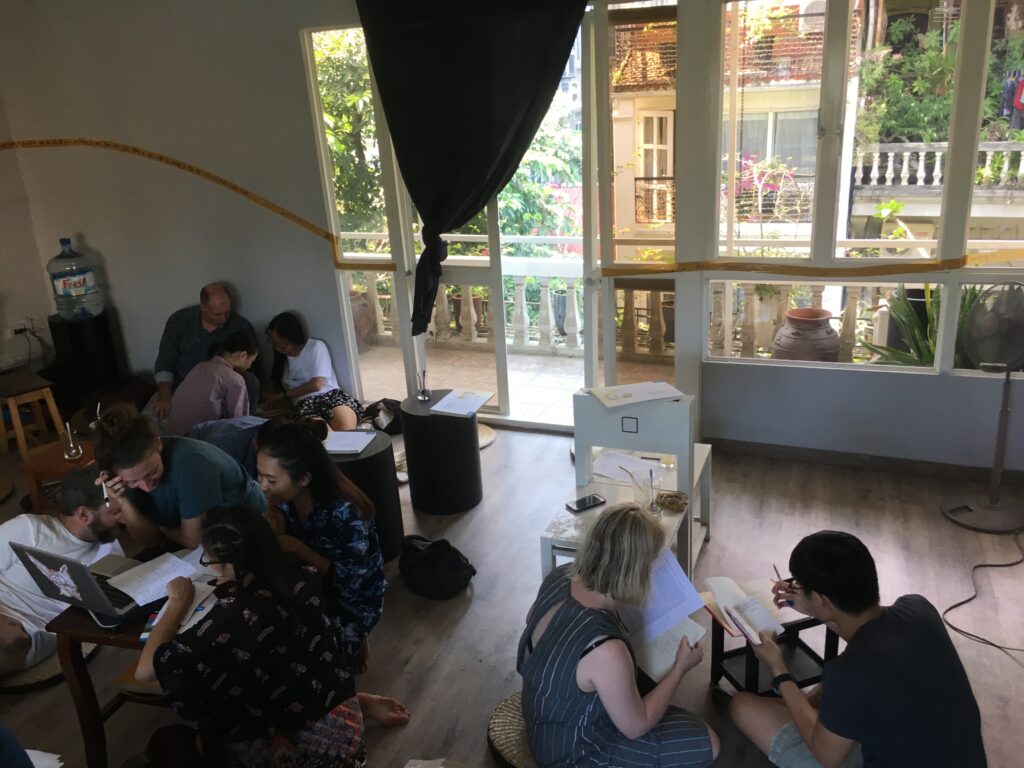

After a mostly sleepless night, we had a day full of panel discussions at Manzi Art Space, discussions that ran into each other: first translation visibility (an all-male panel) flowing into an all-female panel on gender hosted by Ellen Van Neerven, who talked about the role of genders in her indigenous Australian community, which flowed eventually into nationality: Linh Dinh says the nation is the language, and the Singaporeans (Joshua Ip and Tse Hao Guang) say they then wouldn’t have a nation. (But they clearly do – and we Americans identified most somehow with Singapore’s sense of plurality/rootlessness.)

A whole day of panels in English (with Vietnamese infusions by the occasional non-English-speaking Vietnamese panelist) where the question of the role of English and why we were here speaking it kept returning.

14 October: Hanoi

The big day.

My alarm failed me and I awoke on my own with ten minutes to shower before our morning egg bánh mì, which we consumed at the same stand as every day: they recognized us, immediately got out stools, and asked the gestural equivalent of “The usual?”. Greg is obsessed. He ate a total of four bánh mìs today. (I had three, two of them in rapid succession.)

We arrived at today’s art space, Huong Ngo, on a road that sold silk, not knowing where the space began or ended. The rooms led into each other by way of narrow spiraling staircases and branched off in unexpected directions. The first time I searched for the bathroom, I found what seemed like a locked dungeon. Each of the other times, I had to wander around until I found it again. There was also a roof terrace connected to none of the others, not even by any of the many secret passageways.

Technical difficulties should have been expected. The cables on hand could not communicate with the projector, so the café lent us an ancient computer with a dysfunctional trackpad. I was quickly rattled, also by what felt at first like an empty room, but folks filtered in and I regained my cool. We were so ready and we had put so much thought into each slide of this silly slideshow, as we explained the categories of untranslatable texts we’d identified with recordings from Cathy Park Hong, Kurt Schwitters, etc.

But the real excitement was watching everyone spring into action, grab a poem and immediately get to work. Each group had its own approach, which they decided on almost right away. I walked around recording little interviews with my cell phone. Translations into Vietnamese, Austro-Singlish, Chinese, German (me and Greg), and Spanish.

For lunch, bún chả! Oh boy. The grilled meats here are amazing.

*

During the break, we tried and failed to correct my name from Jake to Jacob for tomorrow’s plane ticket.

*

The reading was a three-hour marathon: first a dance performance by Patrick, and then a long list of all of us. But everyone’s poetry is just so good!

*

A wagonload of cops were clearing out the street after curfew. The bánh mì stand where we were eating with Anika (instead of Mexican food) turned out their portable light fixture, made an excuse that we were the last customers, then turned the light straight back on when the cops left.

We still hadn’t gotten on a moped taxi, so when some random guy offered us a ride, we took it. So strange cuddling up so closely on one side to a man I’d never met and, on the other side, to Greg, who was hanging onto my shoulders for dear life as I grabbed his knees, his feet sort of resting on the muffler.

Then when we arrived, the guy refused to tell us a price, just said “You first.” We gave him all the non-major bills we had and he kept complaining and would not take our money. Intense bluffing game. Greg is great at this though, and we prevailed.

15–16 October: Saigon

As feared, Jake Schneider’s ticket wasn’t valid for Jacob so we had to buy another ticket at the airport.

Saigon is modern, tall, commercial, with wide streets: whole lanes for the swarms of mopeds. I immediately missed Hanoi’s human scale, the sense that neither communism nor capitalism had quite penetrated its commercial ethic. (Which Kaitlin puts down to the city’s pride.)

*

Another reading at another art space. A painting by a famous Vietnamese artist of a warring party: one infantryman mounted on a giant turtle, others on a two-wheeled Jeep. In the bathrooms, tasteful oil paintings of couples having sex. There were special cocktails for the occasion with ingredients like kumquat and overpowering wasabi.

A day later, most of the reading merges into the general blur. I do recall my embarrassing moment afterwards, in the open mic, trying to perform Ron’s “provinz à la trance” to actual trance music. It completely cleared the room. Greg rescued me by doing his public/private poem and asking us all to perform public or private personas. I took the chance to be private, tucked my head in the back corner, hid behind the dancers.

Afterwards, Greg, Josh, Hao, Emily, and I all went out for some bánh mì. Greg ate two in a row again.

*

This morning’s panel on publishing strategies was crowded, with hardly an audience. I was so impressed by the other projects (and their sexy websites): Hao’s Zoo, Eliza’s InterSastra, and Josh’s empire.

The other panel was on the role of international English in writing. Then a workshop with Dinh Linh about street poetry and another Translation Lab with Kaitlin where we did transgressive translation strategies. A dissident poet showed up for an impromptu reading – apparently he hadn’t read in public for 15 years.

*

Greg and I each took GrabBikes from The Factory to the space where AJAR had been staying and was holding an intimate launch of their new issue, Parallel. The bike was the best experience ever and made me determined to learn how to ride despite what everyone says. The city is so loud and bright and happening and polluted, with the wind rushing in your face and eyes as you try out different ways to hold on, feel like part of the mass of these 1–2 person vehicles swarming and weaving uninterrupted by cars, condensing to a stop at intersections.

Dinner was dried shrimp/shredded green mango salad, Tiger beer, a fried sparrow, some ribs, and fried rice served in a lotus leaf.

Then back at the little launch, we all sat on the floor in a circle and passed around two copies of the AJAR issue, reading originals and translations in turns or simultaneously.

*

Soon it was time for our final hurrah, unfortunately on Saigon’s most annoying party street. Indescribably obnoxious pop music, table dancing, teenagers feeling cool. Kaitlin rolled her eyes and wished we were anywhere else. I had a heart-to-heart with her in that unlikely space about her decision to go back to New York, the ups and downs of publishing in our two cities, and other gripes, over snails in lemongrass sauce and razor clams with green beans and garlic.

One last big group hug with everyone. I felt seriously sad to say goodbye after just five days. The comedown will be intense.

Travel funded by the Berlin Senate Department for Culture and Europe