Menu

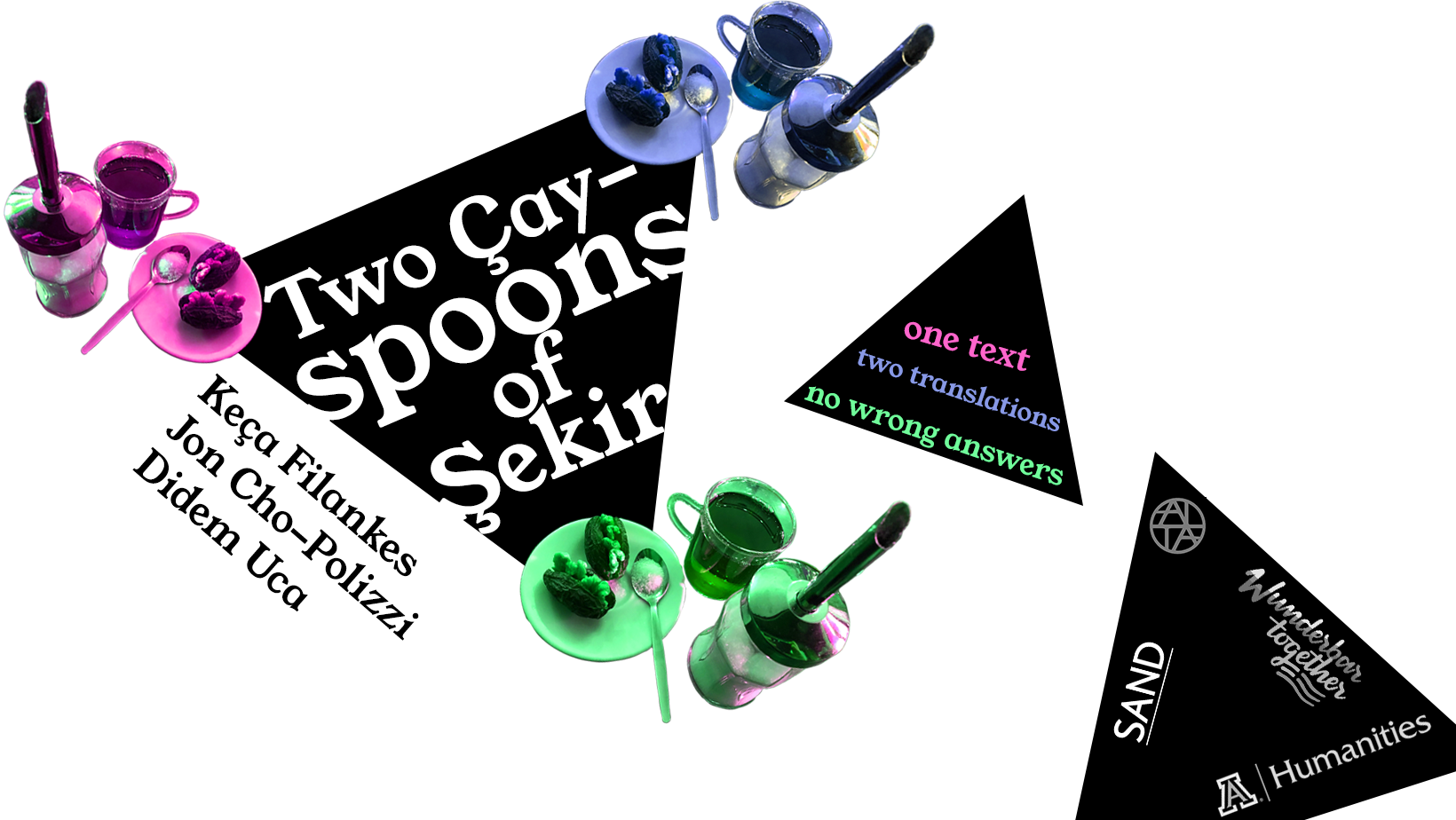

One Poem, Two Translations

For the German-English Translation Slam on International Translation Day 2021, two translators, Jon Cho-Polizzi and Didem Uca, completed their own independent English translations of the same poem by Bîşeng Ergin, alias Keça Filankes, and discussed them live on Zoom. You can read all three versions of the text – the original German version and the two English translations – below. A replay of the event is available to watch for free on Crowdcast.

The translation slam was a collaboration between ALTA and SAND, sponsored by Wunderbar Together, and affiliated with the Tucson Humanities Festival at the University of Arizona in the US. The German poem in question originally appeared in the sold-out “Sprache” (language) issue of the journal Literarische Diverse.

Zwei

Çaylöffel

Şekir

Poetry by

Keça Filankes

1.

„isch will nich däutsch rigtich schrayben

müsssen. ich willl imma nua klayn

schrayben und one regeln wayl ia mich

trotsdem veaschdet. mayne schbrache

gehöat mia. isch bin di schbrache. ich

bin nicht weniga däutsch wayl ich

andas spreche unt schraybe. Ich binn di

deutsche schbrache. Si begind mit mia

unt endet mit mia“

2.

Lost in cultural translation ist,

wenn im Backbuch steht

zwei Teelöffel Zucker

und ich

zwei Çaylöffel Şekir

benutze

und mich

wundere, warum

mein Kuchen nicht süß genug ist.

3.

Meine Muttersprache ist die Sprache,

die meine Mutter sprach, als sie mich

bekam

und in meiner Muttersprache,

also der Sprache, die meine Mutter

sprach, als sie mich bekam

heißt schwanger „ducani“:

2-seelig.

Als mir meine Mutter ihren Körper lieh,

hatte sie 2 Herzen in sich,

teilte diese auf und gab mir eine Seele

und eine Sprache.

Noch bevor ich sprechen konnte, hatte

ich eine Muttersprache:

die Sprache meiner Mutter.

4.

Ich lerne auf einer Sprache zu

sprechen.

Meine Muttersprache, die Sprache, die

meine Mutter sprach, als sie mich zur

Welt brachte, so wie ihre Mutter, also sie

sie zur Welt brachte

Ich lerne auf einer anderen Sprache zu

sprechen.

Deutsch, die Sprache, die meiner Mutter

fremd ist, als ich von ihr und meinem

Vater nach Deutschland geflüchtet wurde.

„Mama, ich will malen.“

Sie versteht nicht, was ich will.

„Mama, ich will malen.“

Sie versteht einfach nicht, was ich will.

„Mama, ich will malen.“

Sie ist verzweifelt, machtlos, wütend.

„Mama, ich will malen.“

Als meine Mutter mit ihren Händen

antwortet, weine ich. Sprache kann sehr

gewaltvoll sein.

Ich höre das Wort „Yabancı düşman“, es

ist nicht meine Muttersprache. Es ist

nicht die fremde Sprache Deutsch. Es

ist die Sprache, die wir nur verstehen

wollen, wenn wir uns schützen müssen.

Yabancı düşman heißt Ausländerfeinde

auf Türkisch.

Deutsch ist ihr auch nach Jahren noch

fremd.

Nicht nur neue Wörter, auch neue Dinge

muss sie lernen.

Ich frage meine Mutter:

„Wo ist das Geodreieck von Büşra?“

Sie versteht nicht, was ich will.

„Es war gerade doch noch hier.“

Sie versteht einfach nicht, was ich will.

„Büşra hat es hier vergessen.“

Sie ist überfordert, nervös, verunsichert.

Alle schauen sie an.

Ich fordere meine Schwester auf, ihres zu

holen.

Als meine Mutter ihres sieht, weiß sie, wo

Büşra’s Geodreieck ist.

Meine Muttersprache ist unsere

Verbindung,

dort wo Deutsch neue Wörter schafft.

Dort, wo Deutschland neue Wörter schafft.

„Hier, nimm diese 5 Mark, geh zum Kiosk.

Kauf mir eine Telefonkarte.“

Was ist eine Telefonkarte?

„Ich brauche die, um in die Heimat

anzurufen.“

Und wo ist diese Karte?

„Frag einfach den Mann im Kiosk nach der

Karte, wo die Banane drauf ist.“

Und was ist, wenn es keine gibt?

„Doch, doch. Es gibt dort diese Karten. Die

Anderen kaufen sie auch dort. Ich muss

deine Tante anrufen.“

Meine Mutter bringt in Deutschland mehr

Kinder zur Welt. Sie bekommen eine

Muttersprache in einem fremden Land.

Sie bekommen eine große Schwester, die

noch eine andere Sprache kann.

„Mach mir einen Termin für diese Woche.

Warum geht das nicht? Sag, dass es

dringend ist. Sag, dass ich das letzte Mal

zwei Stunden gewartet habe. Frag sie,

ob es nachmittags geht. Ich habe kleine

Kinder.”

„Frag den Arzt, was ich machen kann,

damit es ein Junge wird.“

Ich bin höflich und höre dem Arzt

geduldig zu. „Was sagt er denn? Was sagt

er?“

„Frag den Arzt, ob er schon weiß, was es

sein wird. Ist es ein Junge?”

Ich bin ungeduldig. So viele Fragen, so

viele Antworten. So wenig Worte.

„Ich habe Schmerzen da unten und es

juckt mich so, woran liegt das.“

Ich schäme mich. Ich habe Angst.

Ich lüge.

„Frag ihn, ob er sicher ist, dass es ein

Mädchen ist.“

Ich bin genervt. Ich lasse Wörter weg.

„Ist alles normal beim Baby? Warum

hustet deine kleine Schwester so?”

Ich will, dass sie aufhört, mich zu

unterbrechen.

Ich will, dass sie aufhört, weiter Fragen

zu stellen.

Ich besuche meine Eltern, als ich schon

studiere.

Ich skype mit einer Freundin in Peru und

trinke aus einer Flasche.

„Warum trinkst du denn Pepsi light?“

Ich schmunzele. Meine Mutter

verwechselt sowas oft.

Pepsi light. Eistee ohne Zucker. Wurst mit

Schweinefleisch.

Sie kann nicht lesen, antworte ich.

Mit jedem Kind ein kurz anhaltender Elan,

lesen zu lernen.

Aber auf welcher Sprache denn?

Ich kann jetzt auf 5 Sprachen schreiben

Meine Mutter kann es auf keiner

Sie ist Analphabetin

Ich bin 23 Jahre alt und große Schwester

Meine Mutter ist wieder schwanger

Sie hat mit mir 6 Töchter, das 7. Kind wird

ein Sohn werden.

Ich studiere an der Uni und lese sehr

komplizierte Text, auch auf Englisch

Meine Mutter kann nicht lesen, unsere

Namen kann sie, alle Telefonnummern

weiß sie auswendig.

Sie ist Hausfrau, war das immer, und

Mutter. Sie gab mir meine erste Sprache.

Two

Çayspoons

of Şekir

Translated by

Didem Uca

1.

“i don wanna hafta rite jerman

korrektly. i jus wannna all wayz rite

lowrkase an withowt roolz cuz u

understan mee n e way. my langwij

belongz too me. i am tha langwij. i am

no les jerman becuz i

speek an rite difrently. I amm tha

german langwij. It beginz wit mee

an endz wit mee.”

2.

Lost in cultural translation is

when the baking book says

two teaspoons of sugar

and I

use

two çayspoons of şekir

and then

wonder why

my cake is not sweet enough.

3.

My mother tongue is the language

my mother spoke when she

had me

and in my mother tongue,

that is, the language my mother

spoke when she had me,

pregnant is called “ducani”:

2-souled.

When my mother lent me her body,

she had 2 hearts inside,

split them apart and gave me a soul

and a language.

Even before I could speak, I had

a mother tongue:

the language of my mother.

4.

I learn to speak in one

language.

My mother tongue, the language

my mother spoke when she brought me

into this world, just as her mother when she

brought her into this world.

I learn to speak in another

language.

German, the language that is foreign to

my mother, when I was taken by her and my

father to Germany to seek refuge.

“Mama, I want to paint.”

She does not understand what I want.

“Mama, I want to paint.”

She simply does not understand what I want.

“Mama, I want to paint.”

She is desperate, powerless, irate.

“Mama, I want to paint.”

When my mother answers with

her hands, I cry. Language can be so

full of violence.

I hear the word “Yabancı düşman,” it

is not my mother tongue. It is

not the foreign language German. It

is the language that we are only supposed

to understand when we must protect ourselves.

Yabancı düşman means xenophobes

in Turkish.

Even after many years German is still

foreign to her.

Not just new words, she also has to learn

new things.

I ask my mother:

“Where is Büşra’s triangle ruler?”

She does not understand what I want.

“It was here just a second ago.”

She simply does not understand what I want.

“Büşra forgot it here.”

She is overwhelmed, anxious, bewildered.

Everyone is looking at her.

I ask my sister to go fetch

hers.

When my mother sees it, she knows where

Büşra’s triangle ruler is.

My mother tongue is our

connection,

there where German creates new words.

There, where Germany creates

new words.

“Here, take this 5 Mark bill, go to the kiosk.

Buy me a phone card.”

What’s a phone card?

“I need one in order to call

home.”

And where is this card?

“Just ask the man in the kiosk for the

card with the banana on it.”

And what if there aren’t any?

“They’re there. The cards will be there. That’s

where the others buy them. I have to

call your aunt.”

My mother brings more children into the world

in Germany. They are given a

mother tongue in a foreign land.

They are given a big sister who

can speak another language still.

“Make me an appointment for this week.

Why won’t that work? Say that it’s

urgent. Say that last time I

waited two hours. Ask them

if afternoons work. I have small

children.”

“Ask the doctor what I can do

so that it’s a boy.”

I am polite and listen to the doctor

patiently. “What is he saying now? What’s

he saying?”

“Ask the doctor if he already knows what it’s

going to be. Is it a boy?”

I am impatient. So many questions, so

many answers. So few words.

“I have pain down there and it

itches so much, why is that.”

I feel shame. I feel fear.

I lie.

“Ask him if he’s sure that it’s

a girl.”

I’m annoyed. I leave out words.

“Is everything with the baby normal? Why

is your sister coughing like that?”

I want her to quit

interrupting me.

I want her to quit carrying on

asking questions.

I visit my parents when I am already

in college.

I skype with a friend in Peru and

take a sip from a bottle.

“Why are you drinking Diet Pepsi?”

I smirk. My mother

often gets stuff like this mixed up.

Diet Pepsi. Sugar-free iced tea. Pork

sausage.

She can’t read, I respond.

With each child, a short-lived vigor

to learn how to read.

But in which language?

I can now write in 5 languages

My mother can in none

She is an illiterate

I am 23 years old and big sister

My mother is pregnant again

Including me she has 6 daughters, the 7th child will

be a son

I study at the university and read very

complicated texts, in English, too

My mother doesn’t know how to read, our

names, all the phone numbers

she knows by heart.

She is a housewife, always was, and

mother. She gave me my first language.

Two

Çayspoons

of Şekir

Translated by

Jon Cho-Polizzi

1.

“ay down wannna half too rayt propper

Jermen. i wannna all-waze jus rayt

smol en weef-owt rules bee-cuz yew kann unter-stan

mee en-ee-waze. may speach

bee-longs too mee. i yam da lang-wich. I

yam nott les Jermen bee-cuz i speek

en rayt di-friendly. I yam da

Jermen lang-wich. She bee-gens en

ands wiff mee.”

2.

Lost in cultural translation is

when the recipe says

two teaspoons of sugar

and i

use

two ҁayspoons of şekir

and then

wonder why

my cake’s not sweet enough.

3.

my mother tongue is the tongue

my mother spoke when she had

me

and in my mother tongue

that is the tongue my mother

spoke when she had me

“ducani” means pregnant:

with 2 souls.

When my mother lent me her body

she had 2 hearts inside of her

she divided these and gave me one spirit

and one tongue.

Before I could ever speak, I

had a mother tongue:

the tongue of my mother.

4.

I learn to speak a

language.

My mother tongue, the tongue my

mother spoke when she brought me into

the world, like her mother when she

brought her.

I learn to speak another

language.

German, a language foreign to

my mother when I had to flee with her and my

father to Germany.

“Mama, I want to draw.”

She doesn’t understand what I want.

“Mama, I want to draw.”

She just doesn’t understand what I want.

“Mama, I want to draw.”

She is desperate, powerless, enraged.

“Mama, I want to draw.”

When my mother answers with her

hands, I cry. Language can be

so violent.

I hear the word “Yabancı düşman,” it’s

not my mother tongue. It’s

not this foreign German language. It

is the language we should only

understand when we need to protect ourselves.

In Turkish, yabancı düşman means

xenophobes.

Even after years, German remains foreign

to her.

It’s not just new words, but also new things

she needs to learn.

I ask my mother:

“Where is Büşra’s triangle ruler?”

She doesn’t understand what I want.

“It was just here.”

She just doesn’t understand what I want.

“Büşra left it here.”

She’s overwhelmed, nervous, insecure.

Everyone stares at her.

I tell my sister to go get

hers.

When my mother sees it, she knows where

Büşra’s triangle ruler is.

My mother tongue is our

connection,

there where German makes new words.

There, where Germany makes new

words.

“Here, take these 5 marks and go to the kiosk.

Buy me a calling card.”

What is a calling card?

“I need it to call back

home.”

And where is this card?

“Just ask the man at the kiosk for the

card, the one with the banana on it.”

And what if they don’t have one?

“They will. They have these cards there. The

others buy them there, too. I need

to call your aunt.”

My mother brings more children into

the world in Germany. They receive a

mother tongue in a foreign land.

They get a big sister who

speaks another language, too.

“Make me an appointment for this week.

Why won’t that work? Say that

it’s urgent. Say last time I waited

for two hours. Ask them

if afternoons work. I have small

children.”

“Ask the doctor what to do so that

it will be a boy.”

I’m polite and listen to the doctor

patiently. “What did he just say? What did he

say?”

“Ask the doctor if he already knows what

it will be. Is it a boy?”

I am impatient. So many questions, so

many answers. So few words.

“It hurts down there and it

really itches, why is that?”

I am ashamed. I am afraid.

I lie.

“Ask him if he’s sure that

it’s a girl.”

I am annoyed. I leave out words.

“Is everything okay with the baby? Why

does your little sister always cough?”

I want her to stop

interrupting me.

I want her to stop asking

further questions.

I visit my parents while studying

at university.

I skype with a friend in Peru and

drink from a bottle.

“Why are you drinking Diet Pepsi?”

I smirk. My mother

often mixes up these things.

Diet Pepsi. Sugar-free iced tea. Sausage made from

pork.

I tell her she can’t read.

With every child, a little push

to learn to read.

But which language should it be?

I can now write in 5 languages

My mother can write none

She is illiterate

I’m 23 years old and a big sister

My mother is pregnant again

Including me she has 6 daughters, the 7th child will be

a son.

I’m studying at university and reading very

complex texts, in English, too

My mother cannot read, she knows

our name, she’s memorized the phone numbers

by heart.

She is a housewife, always was, and a

Mother. She gave me my first tongue.

Poet & Translators

Bîşeng Ergin alias Keça Filankes (poet) holds degrees in International Relations/Peace and Conflict Studies, Sociology, and Political Science from Goethe University Frankfurt. Her parents fled from Turkey when she was a baby, and today as a Kurdish woman, political educator, and social justice activist, she dedicates her political life to fighting against discrimination, fascism, and war in solidarity with refugees and migrants. She writes poems and performs spoken word as part of Literally Peace, a transcultural German and Syrian collective.

Didem Uca (translator) is Assistant Professor of German Studies at Emory University. Her research focuses on post/migrant cultural production, with recent and forthcoming articles and translations in Seminar, TRANSIT, Monatshefte, and Die Unterrichtspraxis. She is co-editor of Jahrbuch Türkisch-Deutsche Studien and serves in leadership roles in WiG, DDGC, and the MLA.

Jon Cho-Polizzi (translator) is an educator and freelance literary translator. He studied Literature, History, and Translation Studies in Santa Cruz and Heidelberg, before receiving his PhD in German and Medieval Studies at UC Berkeley with a dissertation titled “A Different (German) Village: Writing Place through Migration.” He lives and works between Northern California and Berlin.

Original Publication

Keça Filankes’s poem was originally published in German under the title “Zwei Çaylöffel Şekir” in the “Sprache” (Language) issue of the journal Literarische Diverse.

Founded by Yasemin Altınay (she/her) in 2019, Literarische Diverse Verlag publishes magazines and books that promote equity in literature and defend the tradition of self-empowerment. The project puts Germany’s colorful realities on paper – forever legible, forever part of the whole – and gives preference to BIPoC and LGBTIQ* voices.

Organizers, Sponsors, and Affiliated Festival

Initiator, co-curator, and co-organizer as part ALTA44

Co-curator and co-organizer

Sponsor

Tucson Humanities Festival of the University of Arizona